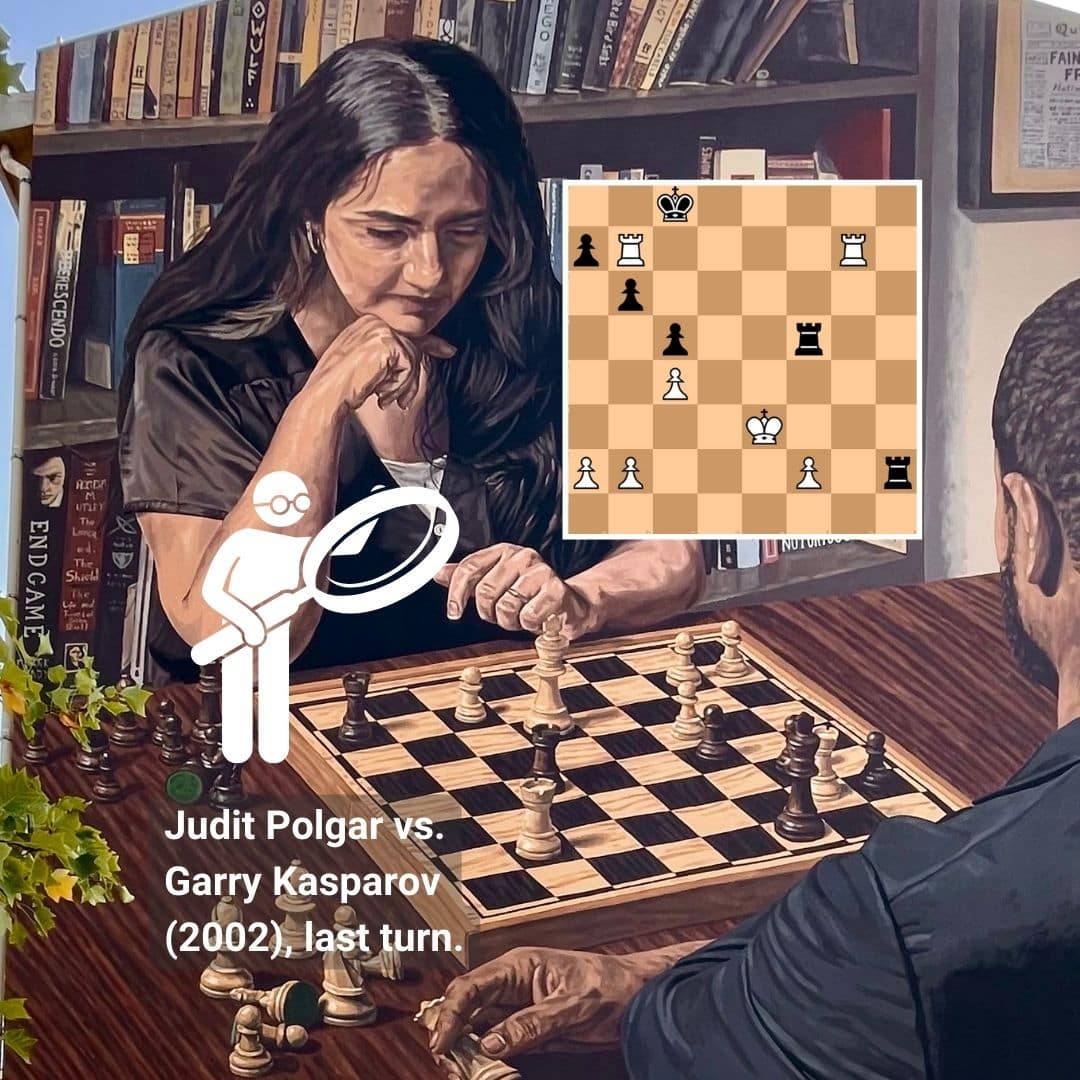

In the vibrant neighbourhood of Zambujal, in Lisbon, Portugal, a mural stands as a testament to SDG 5 – Gender Equality. Created by artist Mariana Duarte Santos, the mural is part of an urban art gallery dedicated to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aims to act as an agent of social change and promote sustainability. This intellectual and symbolic artwork utilises the game of chess to convey powerful messages about gender and equality.

The mural features Soraia and Das Neves, two local residents, playing chess. Soraia belongs to the Roma community and is married to Das Neves, who is from a Cape Verdean family. Their inclusion highlights the mural’s deep connection to the local populace, making it a piece of art that resonates with the community’s identity and struggles.

Mariana chose chess for its representation of strategic conflict, akin to the ‘gender war’ often discussed in contemporary society. The game’s focus on victory and defeat mirrors the adversarial nature of gender debates, suggesting that such a win-lose mentality does little to benefit either men or women. Through this analogy, the mural critiques the often zero-sum perception of gender issues.

The pieces on the chessboard mirror a significant game of chess between Chess Grandmasters Garry Kasparov and Judit Polgar, with the pieces positioned to reflect Polgar’s victory over Kasparov in 2002. This victory is symbolic, as Kasparov, one of the world’s greatest players, had once said that there was “real chess and women’s chess”. Polgar’s triumph was a powerful reminder of women’s capabilities and achievements when given the opportunity in traditionally male-dominated fields.

Beyond the chessboard and players, the mural’s background features influential figures and texts on gender equality. Notable books like “Notorious RBG” highlight Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s advocacy for both women’s and men’s rights. There is a newspaper article about Amelia Earhart, the pioneering aviator and women’s rights activist whose insistence on equality and independence in her marriage during the 1930s echoes the mural’s broader themes of gender equality and personal autonomy. There is also a reference to “Nüshu”, a unique script created by women in 18th-century China who were barred from learning to read or write. This secret, phonetic script allowed women to communicate and support each other in a patriarchal society, symbolising resilience and solidarity. Many other famous names fill the rest of the background.

Women in Chess

Chess is an intellectual sport where men and women compete on equal footing, symbolising the potential for gender parity. Yet, it has historically been male-dominated.

Thankfully, men-only tournaments no longer exist, and women can compete in any competition. Women have made significant strides in chess, challenging stereotypes and breaking barriers. Judit Polgar, a Hungarian Grandmaster and the highest-ranked female player in history is a prime example of this by successfully competing against the world’s top male players, demonstrating that women could excel in chess at the highest levels.

Despite these accomplishments, women still face significant disparities in chess, such as lower prize money, fewer sponsorship opportunities, and general underrepresentation. To address these issues, numerous organisations and initiatives worldwide are dedicated to promoting female participation in chess. These efforts strive to create more inclusive environments and provide opportunities for women to thrive. Prominent female players, such as Women’s World Champion Ju Wenjun, and famous chess streamers like Anna Cramling and Maria Emelianova, inspire new generations of girls to take up chess and pursue excellence.

A silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic was the surge in popularity of chess worldwide. The launch of the TV series ‘The Queen’s Gambit’, along with the growth of online chess and the streaming of chess games during lockdown, led to a boom in the game’s popularity.

The Evolution of the Queen

Chess pieces have also evolved over time, with changes attributed to the Queen, the most powerful piece in modern chess, intertwined with the game’s history and societal changes. In the early versions of chess in India and Persia, the piece corresponding to the Queen was known as the “fers” or “vizier,” a male figure whose name roughly translates to advisor. It was a relatively weak piece that could move only one square diagonally.

When chess reached Europe in the 9th century, the ‘vizier’ and ‘elephant’ pieces were rebaptised into the Queen and the Bishop. It would, however, only be in the late 15th century that the Queen would evolve into the formidable chess piece we recognize today. This change coincided with the rise of powerful queens in European history. Marilyn Yalom and H.J.R. Murray, who have both written on the topic, agree that the likeliest explanation for this metamorphosis was the reign of Queen Isabella of Castile and León (1474), who ruled jointly with her husband Ferdinand and was known for her strong leadership and influence. The enhanced abilities of the chess queen to move any number of squares vertically, horizontally, or diagonally reflected these historical shifts and symbolized the increasing recognition of women’s power and influence.

The evolution of the Queen parallels broader societal changes where women’s roles were increasingly acknowledged and respected. With her unrivaled range of movement, the modern chess queen showcases women’s potential and strength when given equal opportunities. This historical evolution not only highlights women’s emerging roles in society but also resonates in global celebrations such as World Chess Day, which aims to underscore chess’s role as a platform for advocating gender equality and showcasing the intellectual prowess of all participants, regardless of language, age, gender, physical ability, or social status.

The SDG5 mural in Portugal and the evolution of chess through history both serve as powerful symbols of gender equality, encouraging a reexamination of gender roles and inspiring ongoing efforts toward a more equitable society.