Léonie d´Aunet was the first woman in history to visit the Svalbard archipelago. In 1839, it was portrayed as a visit to the North Pole. Although Svalbard is 1,000 kilometres away, the polar ice rim at the time touched the islands and drift ice filled its bays and fjords. Fast forward 170 years, when United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon visited the islands in the run up to the 2009 COP15 Climate Conference in Copenhagen, these same bays were virtually ice-free.

The then Secretary-General’s choice of visiting Svalbard to plead climate action was no coincidence: nowhere on the planet is heating faster. The Arctic has warmed almost four times faster than the rest of the globe, and Svalbard even more rapidly. While the Earth is approximately 1.1⁰C warmer than at the beginning of the industrial revolution, temperatures have risen in Svalbard by 4⁰C since 1971, or in just over half a century.

7-10 ⁰C increase by 2100

Whilst Léonie d´Aunet was the first woman on Svalbard, Norwegian, Dutch, English, and French whalers – who are traditionally male – had for centuries used the islands as a base for whaling. Svalbard went under the name of Spitzbergen, which is one of the archipelago’s islands, until it fell under the sovereignty of Norway in 1925.

Léonie D´Aunet described the moment when she set foot for the first time on the ground at Magdalena Bay: “I said on the ground, as one usually does, but I should have said on snow, because I couldn’t see the slightest part of earth,” she wrote in her book Voyage d’une femme au Spitzberg (1854).

Even in summer, everything was covered in snow and “between each mountain there are glaciers, which are growing in height every year. This is inevitable: the immense amount of snow that piles up during the 10-month winter cannot change in the summer that lasts only for some weeks. Eventually, in time the glaciers will be as high as the surrounding granite peaks.”

The French woman’s predictions have, of course not materialised.

The Norwegian Environment Agency predicted in a that under medium to high scenarios for future climate gas emissions, annual air temperature will increase by an astonishing 7 ⁰C-10 ⁰C before 2100. The glacier area and mass will be severely reduced during the 21st century and will contribute to global sea-level rise.

Capturing Svalbard’s splendours through art

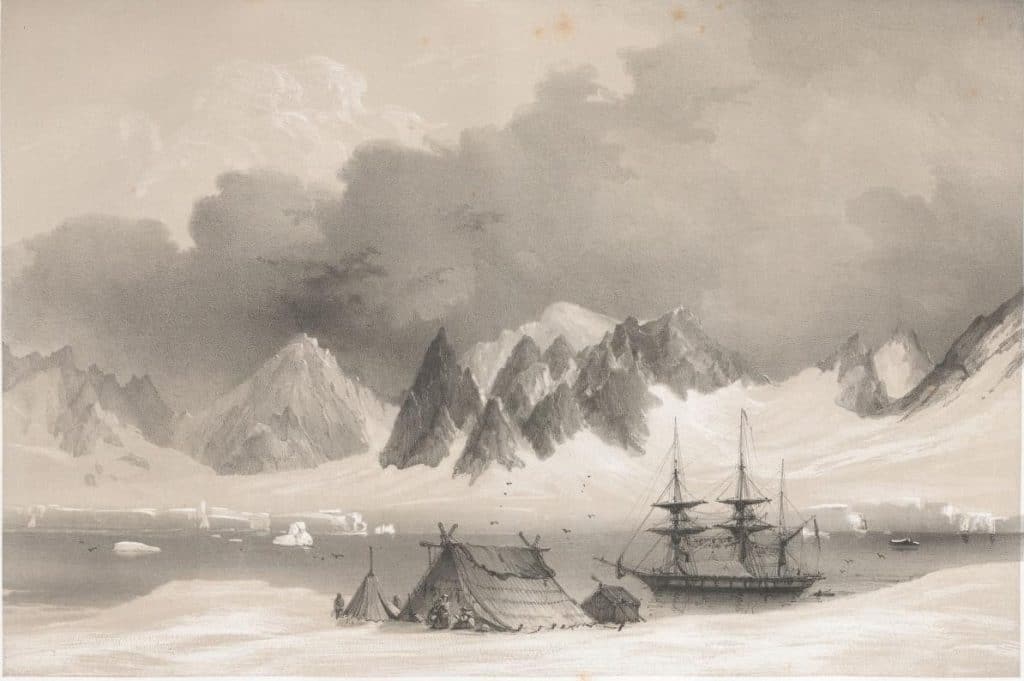

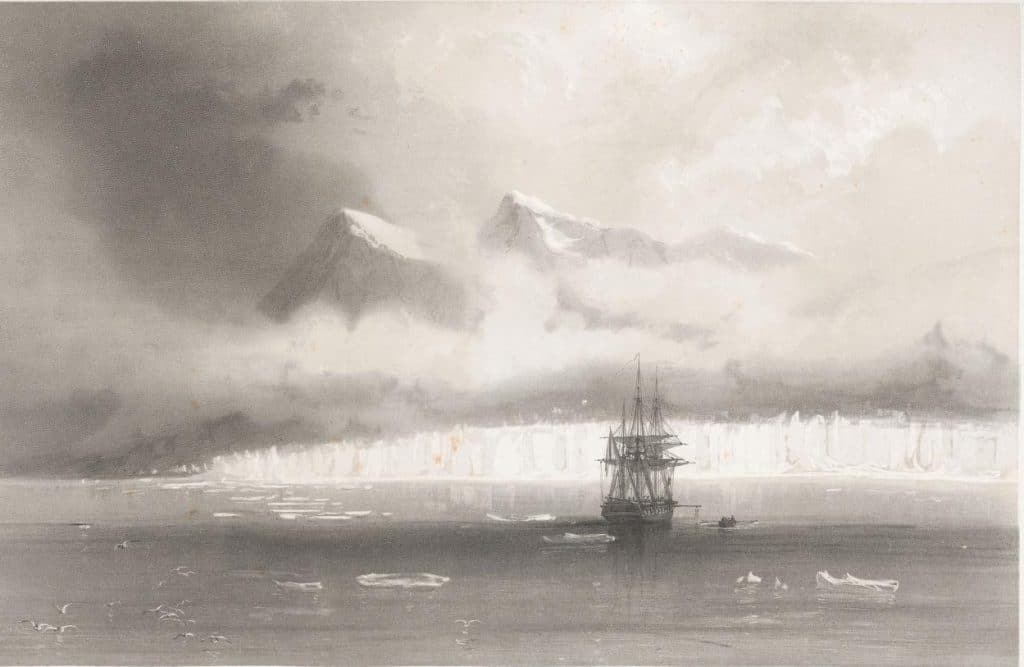

Léonie D’Aunet´s voyage to the Polar region was part of the so-called “La Recherche expedition” led by French naturalist Paul Gaimard. She travelled with her husband François-Auguste Biard who, along with Auguste Mayer, was one of the painters accompanying the expedition. It is to them that we owe the art works that show us the splendours of Svalbard around 1840, before climate change kicked in.

When UNRIC interviewed Professor Thomas V Schuler, Professor in the Department of Geosciences of the University of Oslo, he was on an assignment in the University Centre in Svalbard. There, the drawings from the La Recherche expedition embellish the premises.

“We observe that Svalbard glaciers lose mass, especially in the past two decades and apparently at an increasing rate. This is very clear on a qualitative basis,” Schuler says. However, quantifying this is more complicated, since there are regional differences between the northeast and the southwest. “Those in the milder southwest are experiencing strong melting induced mass loss.”

The effects of climate change have already had a deathly impact. An avalanche in 2015 cost two lives in Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost permanent settlement. They were described as Svalbard’s first deaths from climate change.

Despite the fact that fossil fuels, which when burned release CO2 emissions, are warming the planet, coal mining continues on Svalbard and is increasingly lucrative due to the energy crisis and war in Ukraine.

Sea ice may be gone by 2035

Since the 1980s, the amount of summer sea ice has halved, and some scientists fear it will be gone altogether by 2035. What the effects of climate change will have on biodiversity on Svalbard may in some ways be unclear, the fate of polar bears is at stake as the sea ice concentration in the northern Barents Sea substantially decreases.

Back in Paris in the 1840s, d´Aunay had a famous affair with the writer Victor Hugo and subsequently divorced her husband François-Auguste Biard. Some say the King Louis Philippe gave Biard an important assignment in exchange for going easy on Hugo.

François-Auguste Biard’s frescoes on the walls of entrance to the geological department of the Natural History Museum in Paris capture a lost moment in time, displaying the hunting of polar bears and walruses. With the retreating of the polar ice rim around Svalbard, polar bears are already struggling and a 10 ⁰C temperature rise, as predicted by the Norwegian Environment Agency, would change animal life beyond recognition.

If the most dramatic predictions come true, there may indeed not be any polar bears left to paint, at least not in Svalbard.