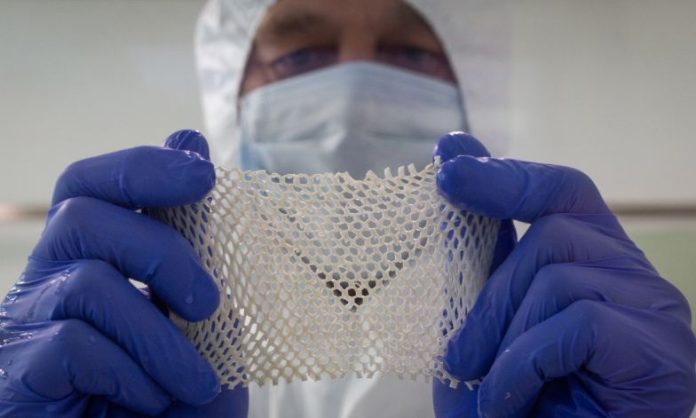

Using cod skin as a replacement for human skin may sound like something out of a science fiction movie. Cod has been an important staple of the diet of Europeans for centuries, but its skin has had little or no value and often ends up in a landfill. Now, however, cod skin is being used to save the lives and limbs of humans.

Amputations

Icelander Guðmundur Fertram Sigurjónsson, who holds university degrees in chemistry and engineering, developed an interest in diabetic wounds and human-tissue trauma while working for a prosthetic company.

Diabetes is a serious global public health problem. According to the World Health Organization 422 million people worldwide have diabetes, and 1.5 million deaths are directly attributed to diabetes each year. In some cases, diabetes reduces the blood flow to the legs and feet, wounds do not heal, and infections are common. In extreme cases, this can lead to amputation. The global annual incidence of diabetes-related amputations is 140 amputations / 100,000 people with diabetes. This means that annually there are almost 600,000 amputations caused by diabetes.

Cod skin healing damaged tissue

Based on his professional experience, coupled with his background in the fishing village of Ísafjörður, Fertram came up with the concept of using fish skin to heal damaged tissue.

“Cod skin is very similar to human skin, with the most substantial difference being that human skin has hair instead of scales,” he told UNRIC.

The skin of human cadavers, pigs and cows has been used for the same purpose, but there are risks that viral diseases can travel between mammalians, such as Creutzfeld-Jacob (Mad Cow disease), pig-influenza and many more. Because of this disease transfer risk, regulatory authorities require intensive chemical treatment of mammalian tissues being used in medical applications.

“The key components of my discovery of using cod-skin to treat human wounds, is that the cod lives at such low temperature that its viruses don’t posses risk to humans and the method of removing the fish-cells from the skin without destroying the skin’s structure,“ Fertram says. “The absence of viral disease transfer risk allows us to process the skins in a gentle manner so that the skin’s similarity to human skin is maintained, while tissues processed from mammalian sources require intensive chemical treatment, that make them dissimilar to human skin,“ Fertram says. “During the processing, the fish-cells are also removed from the fish skin. With the fish-cells, and their fish-DNA being gone, the human body does not recognizing the cod-skin as something alien, and soon after implantation, human cells make themselves at home in the space previously occupied by the fish-cells and convert the cod-skin to human-skin. “

Sustainable methods

No toxic materials are used in the process, which requires water, salts and energy. “Luckily, we have a lot of clean energy here in Iceland,” Fertram explains.

Although the method is sustainable, not to mention the raw material – with cod skin typically discarded – Fertram owes his success to an unsustainable financial situation in Iceland during the financial crisis of 2008 and the disappearance of the shrimp processing industry from Ísafjörður, where he spent summers in his youth with his grandparents. “The processing of shrimps was an important factor in the local economy in the eighties, but due to overfishing, it disappeared,” says Fertram. “Fortunately the management of fishing stocks in Iceland is now much better and guided by sustainability goals.”

The silver lining for Fertram and his hometown, which is only 50 km from the Arctic Circle, is that he acquired an abandoned laboratory formerly used by the shrimp industry. In addition, the Icelandic Ministry of Industry offered advantageous grants for innovative start-ups after the financial crisis.

A growing business

Kerecis was originally founded in 2007 by Fertram and his wife Fanney Kristin Hermannsdottir, a pharmaceutical regulatory consultant, as a vehicle for their consulting activities, but has evolved into becoming the world’s sole manufacturer of regulatory approved medical fish skin products. It now employs over 400 people and has an annual income of $72 million. The market is first and foremost in the United States and Germany and, with a rise in diabetes in the world, there is increased demand for their product.

From Fertram’s previous experience working for Össur, a producer of artificial limbs, he was all too aware of how important it is to prevent the diabetic ulcers that can lead to amputation.

“Not only is it a traumatic experience for the patient and their whole family, but they are even more immobile and dependent on his family, which in turn decreases life expectancy even further. Unfortunately, the life experience of a person who has been amputated is only five years after the operation, which is the equivalent of a patient suffering from colon cancer.”

New projects on the horizon

Recently, the family that owns the Danish Lego brand invested in Kerceris. “This will help us focus more on developing new projects,” Fertram explains. “We are for example developing ways of using cod skin for hernia repair and breast reconstruction, and are also conducting research on the use of cod skin in oral surgery.”

”The fish skin has applicability in the oral cavity when implants, supporting new tooth are inserted into the jaw.” Fertram says and added that oral surgery is also increasingly needed because of popularity of tobacco- and nicotine patches.

Fertram’s innovative projects are an example of some of the sustainable solutions being developed to help the health challenges that many people face, whilst also bringing about a positive economic impact in his economically vulnerable region.